Launch of the GWP-NEWAVE Science Communication Seminar Series

On June 17th, 2022, NEWAVE and our partner Global Water Partnership (GWP) launched a joint initiative for the members of the two networks, addressing the topic of science communication. With a series of informal seminars, the NEWAVE ESRs and the GWP Communication Officers are invited to exchange their experiences, challenges, and expectations on science communication. Diverse communication tools and products will be discussed throughout the series, examining their impact and exploring potential in the water governance domain.

According to its broad definition, science communication can be understood as a “social conversation around science” (Bucchi & Trench, 2021, p. 6). It is the process of translating technical information into messages coherent for those on the receiving end, bridging the gap between the scientific community and the greater public (Cooke et al., 2017). As emphasized by Bucchi and Trench (2021), there seems to be an agreement that “there is a harmful gap between research and practice that needs to be closed” (p. 2).

Fischhoff (2018) argues that this gap tends to be a result of two issues. Bounded rationality, occasionally encountered by the scientific body, entails overlooking issues that cannot be treated systematically, while assuming the ability to still reach significant conclusions within the constraints of one’s discipline. The second issue is practitioners’ satisficing, which consists of relying on imperfect solutions that seem relevant in a given situation and satisfy the minimal expectations.

The gap between science and practice could lead to cases of scientific bias, generalization of scientific results, or a selective absorption of academic findings (Fischhoff, 2018). From this, a call for effective science communication emerged. Its goal is to first and foremost facilitate better-informed decision-making within the audience and to inform, educate, or simply entertain (Bucchi & Trench, 2021; Cooke et al., 2017). To achieve these objectives, science communication requires producing information relevant to decision makers, communicating the knowledge in a coherent manner, ensuring two-way communication channels, and improving the process where necessary (Fischhoff, 2018).

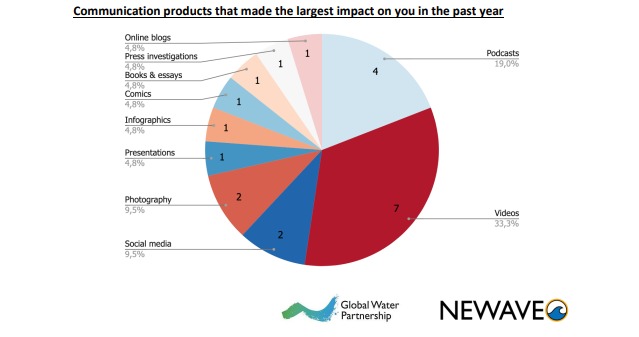

The theme of effective science communication is central in water governance research. After running a survey among NEWAVE’s Early Stage Researchers (ESRs) and Global Water Partnership (GWP)’s Communication Officers, we learned about the key perceived challenges when communicating about water governance. Translating technical content into non-scientific language, while simultaneously avoiding oversimplification and losing the nuance was listed as the top challenge. Other common answers included developing a clear and concise manner of communicating, engaging your audience, and creating attention-grabbing material among others. The full list can be consulted here.

With this in mind, we entered our first science communication seminar ready to discuss these challenges, brainstorm creative solutions, share our experiences and stories, and connect on this topic with GWP, our partner network, led by the objective of improving our knowledge and action on science communication.

As emphasized by the colleagues from GWP, Gergana Majercakova and Monika Ericson, the idea to exchange on this theme came about quite organically, as there is a clear area of synergy between NEWAVE and GWP within the context of communication about water knowledge and science, and, more specifically, on water governance.

During the session, Prof. Emanuele Fantini, the NEWAVE Leader of Work Package 8 on Dissemination, shared his experience in podcasting in water research. In his presentation, Prof. Fantini focused on three processes – listening, editing, and sharing. The first refers to listening to the interlocutor’s voice. Podcasting tends to rely on interviewing others hence the goal here is to listen attentively and learn from your interviewee. When we invite someone on a podcast, we also give them the recognition for their knowledge, showing them that their experience is relevant for a greater audience. In this sense, podcasting can act as an educative tool.

The second process, editing, is where the author’s voice shines through. Being an author, you should be accountable for your choices, as podcast production is both an editorial and a political process. Indeed, there is a responsibility in making the decision on which parts of the material to keep and which to exclude. Lastly, sharing refers here to the process of listening to the audience’s voice. Podcast, as a more intimate, one-in-one medium, requires a larger attention span from the audience. Thus, the content ought not to be too abstract, as it would be hard to follow and hard to visualize. A piece of advice here would be to “write for the ears.”

As a way of closing the session, our NEWAVE Scientific Project Manager Caterina Marinetti posed the final question of: “What main aspect to consider when communicating academic knowledge to a non-academic audience?”. As we completed a round around our virtual room, several constructive ideas were brought up, including:

- Avoiding the jargon in the spirit of “less is more”, making the content digestible

- Making the content relatable and interesting for the audience

- Bringing in the nuance to the discussion

- Understanding who the audience is to select the best-matched communication tools

- Recognizing the preconceptions and what the audience already knows to integrate local knowledge

- Including a plurality of perspectives

- Leaving room for different interpretations, allowing for questions and thoughts instead of providing a finalistic solution

In the concluding part of the seminar, our members indicated their preferred topics for the next appointments. The majority of participants declared that learning about effective and creative communication methods is of most interest. This answer was closely followed by science communication tools (such as story-telling, scientific journalism, policy briefs and more), methods of targeting audiences, and art-science collaboration. With this in mind, we will choose from new aspects to include in the next seminars: presentation of case studies, discussion on successes and failures, and conversation with guest speakers. As the group agreed to meet every four months, the organizing team is preparing the second appointment of the series, which will happen after the holiday break.

Stay tuned to learn more! If you have a specific interest on this topic and wish to connect with us, please leave a reaction below or contact us via our contact form.

References:

Bucchi, M. & Trench, B. (2021). Rethinking science communication as the social conversation around science. Journal of Science Communication, 20(03), pp. 1-11. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.20030401

Cooke S. J., Gallagher A. J., Sopinka N. M., Nguyen V. M., Skubel R. A., Hammerschlag N., Boon S., Young N., & Danylchuk A. J. (2017). Considerations for effective science communication. FACETS, 2, p. 233–248. https://doi:10.1139/facets-2016-0055

Fischhoff, B. (2018). Evaluating science communication. PNAS, 116(16), pp. 7670-7675. https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1805863115