Why aren’t we talking about water?

In this blog entry, ESR 8, Hannah Porada, explains what the gas extraction in the Dutch province of Groningen (The Netherlands) has to do with water and why we still don’t hear about it. She argues for a politicization of water problems related to gas extraction. This entry is a part of the blog series ‘Tot op de bodem’ of the Environment and Society Research Group at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). The blog series looks at gas extraction in Groningen from an interdisciplinary perspective and tries to keep up the political attention for the issues in Groningen until the official results of the currently ongoing inquiry in the Dutch Parliament are made public in February 2023.

The blog has been re-posted from its original source.

About gas and waterflows

It was during the sixth week of the parliamentary inquiry – on October 3, 2022, to be precise – that I made my way from Amsterdam to The Hague to watch the hearings of the day in person. The witness interrogated during the morning, Geert-Jan ten Brink, had called my attention at least as much as Henk Kamp, former Minister of Economic Affairs who would be interrogated later that day. Ten Brink was not only the former mayor of Slochteren but also dyke reeve (Dijkgraaf) at the Waterboard (Waterschap) Hunze en Aa's. At the time of his hearing, I had been investigating the link between gas extraction and water in Groningen for quite some time. I had gained deep empirical insights into gas extraction-related water issues. I had analyzed why so many other gas-related topics were highly politicized, whereas issues related to water management where mostly absent from political debates. Sitting on the train to the Hague, I wondered: Would ten Brink be asked about the implications of gas extraction on the water systems in Groningen at all? If so, what stance would he take on it? But let me take a step back and explain the basics…

What does the gas extraction mean for Groningen’s water?

Almost everyone living in the Netherlands has heard by now about the human-made gasquakes (gasbevingen) in Groningen. I do not have to say more about it: the hardship for the inhabitants of the province, the bureaucratic mess, the technocratic approach, the loss of political trust, and the relationship between fossil-fuel alliance NAM and the Dutch state are only a few items on a long list of hotly debated political topics.

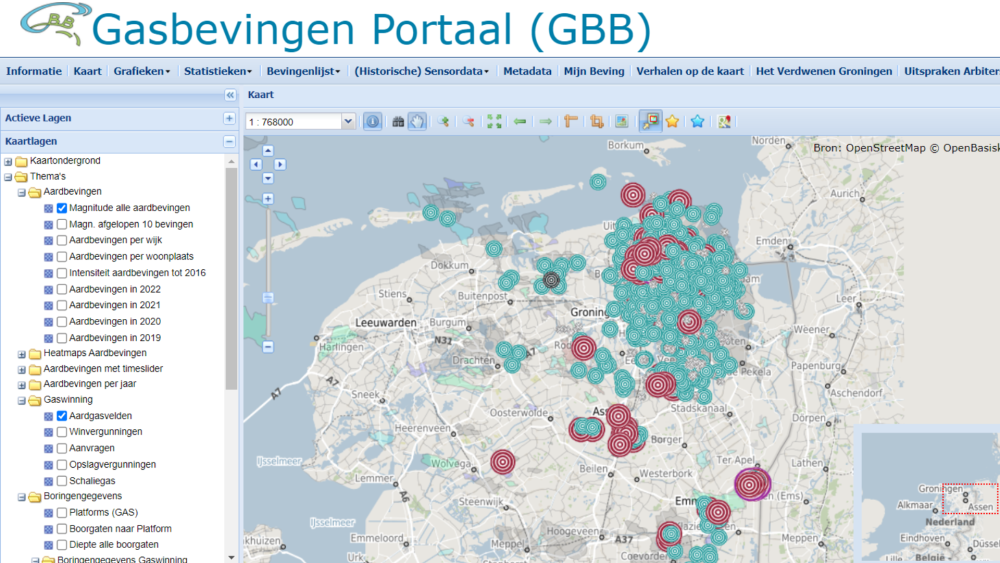

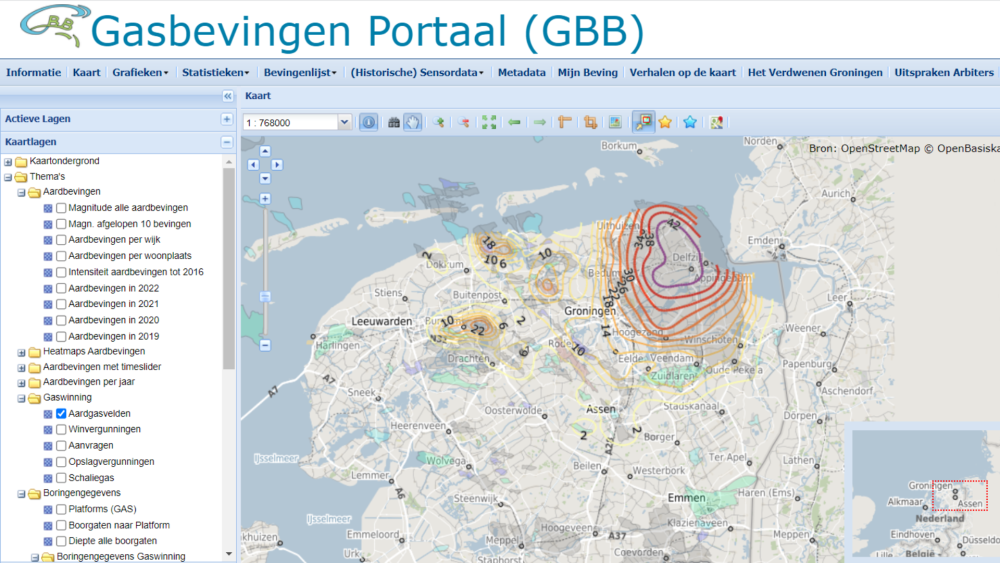

The map illustrating the gas quakes and the following illustrating the land subsidence are created with the mapping tool of the social movement Groninger Bodem Beweging (GBB).

The fact that gas extraction has additionally caused land subsidence (bodemdaling) is also no secret. Subsidence implies that the land above the 900 km2 big gas field sinks unevenly, currently up to 37 cm, with more sinking ahead according to NAM’s predictions. The subsidence complicates the water management in an area where water levels are meticulously controlled, just as in many other parts of the Netherlands. Most severe are the consequences in the catchment area of Waterboard Noorderzijlvest, where 45.000 hectares of land are affected. The waterboard – used to control the water levels according to past agreements between different water users (peilbesluiten) – must re-negotiate new water levels to account for the gas extraction-subsidence. Given the uneven land subsidence in the ‘flat province’, this is a complicated task. The original four sub-catchment areas and canals draining the water to the sea by gravity no longer do their job. Pumps (gemalen) were installed to prevent ‘deeper areas’ from being flooded. Infrastructure such as dikes and bridges were adjusted to the sinking land. The operation of the pumps and other measures taken entailed major costs.

Back in the hearing room, Ten Brink summed up the challenges for water management as follows:

"Water flows naturally towards the sea. The moment the soil subsides [from gas extraction], water may not flow naturally towards it anymore. So you have to constantly adjust your systems to the subsidence, either with pumping stations or putting weirs in a different way. So you are constantly adjusting your systems"

Why don't we hear much about it then?

Despite the ongoing adjustments that ten Brink mentioned, it was rather exceptional that the topic was addressed during the hearing. And even then, he later confessed that the issues of water management had been solved rather well: “That in itself works extremely well“. By that he referred to the compensation fund that had been set up back in time. Two agreements - between NAM and the State and NAM and the Province of Groningen – established the fund for water infrastructure adjustments in 1984 and institutionalized the Land Subsidence Commission (Commissie Bodemdaling). The commission was (and is) responsible for handling subsidence-related claims from institutions such as the waterboards, municipalities, or shipping companies towards NAM. Until the end of 2021, the commission had paid around 240 million euros for claims made according to its 2021 annual report.

The set-up of the commission and the money NAM made available surely did their job to depoliticize the gas extraction-subsidence. While many Groningers (continue to) haggle over every penny of compensation for gas quake damage to this day (first with NAM, now with the government), the ‘technically-justified’ claims by the water boards and other institutions were rarely questioned in their legitimacy. Land subsidence was recognized early on as ‘logical’ consequence of gas extraction (in contrast to the long-denied link between extraction, quakes, and houses). Water management was approached bureaucratically. Fixing the water levels and predicting the future subsidence in Groningen fell into this logic. The ‘technologic fix’ to subsidence made the politics behind the extractive transformation of Groningen’s water systems almost completely invisible.

A ‘critical’ waterboard employee I had encountered doing my fieldwork in Groningen, however, reminded me to reconsider the totality of the ‘technological fix’. He put the subsidence from gas extraction back on the political agenda. He summarized how the technical approach made people unaware of its political implications:

“In the waterboards there is awareness of the soil subsidence, but not about the politics of it”

Diving below the surface of the issue, I ran into further limits, contractions, and contestations of the technical approach to gas extraction-subsidence and water management. Several waterboard employees, for instance, criticized the situation they had been thrown into and expressed their concern about the irreversibility of subsidence in some of their areas of work.

Another contested point was house damage that some Groningers assumed to be the indirect consequence of lowering the water levels due to gas extraction-subsidence. While the Commissie Bodemdaling stated in their 2020 annual report that there was “no causal relationship [...] between the subsidence that occurred and the reported damage to the homes”, other experts indicated that indirect effects of uneven land subsidence on damaged houses were possible. This clash of one ‘technical’ assertion with a ‘counter-assertion’, joined the list in a never-ending story of clashing scientific expertise, truth claims, and counter-claims, and debates around the legitimacy of knowledge. While I have much more to say about this, I want to highlight something specific here: in Groningen uncertainty about ‘what we can know’ is only (!) mobilized against the Groningers, yet another example about how compensations get delayed, while NAM and the government stand by and watch.

A glimpse of the future

Land subsidence will ‘survive’ the gas phase-out. That sparks questions about ‘eternity costs’ for water management, that is to say costs and burdens that arise or remain after the extraction of coal or gas have been phased-out. Nobody – neither NAM nor the Land Subsidence Commission - doubts that these costs will occur. But how high they will be and who will pay for them remains uncertain. During his hearing, ten Brink raised concerns about the future costs of subsidence. He put the issue into perspective by stating: “We are talking about really a lot of money”. Without wanting to disclose any details due to ongoing negotiations between NAM and the waterboard (transparency?), he stated:

"That's also something I'm quite concerned about going forward: what happens if NAM withdraws from the area altogether?"

He also criticized that no one had thought about the eternity costs of subsidence before:

"This is another point where I think: this is not convenient and wise; this should have been organized from the start by the State. You issue a permit for, in this case, taking gas from the ground. That leads to adjustments to the entire infrastructure. What do you do the moment a company no longer uses that permit?"

During my time in Groningen, I came across diverse actors sharing these concerns, warning about a subtle transfer of the financial burden to the public. “We can already anticipate the future costs. But who will pay for them?”

Open questions and a call for solidarity

To finish, I will leave you with this question. And as I return to my initial speculation about ten Brink’s hearing, I must admit that although he did not reveal anything surprising, his statements confirm my claim that we must consider the sinking soils and the water flows in Groningen as deeply political problems. All of this without diminishing the complex and severe daily experience of Groningers who deserve our steady solidarity.